MInneapolis FIRE STATION #24

We acknowledge this is Dakota and Anishinaabe land, ceded in 1851 by The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux under duress and hardship set in place by colonial occupation. This small piece of land is in the watershed of Mníȟaȟa Wakpádaŋ and is a part of the history of the B'dote that perhaps first brought people to this region.

The old firehouse built and commissioned in 1907 as Minneapolis Fire Station #24 is located at the intersection of Hiawatha and 45th Street across from the 46th Street light rail station. The exterior of the building remains true to its first appearance with the addition of a few modern features including glass doors that now mark the entrance and a rooftop billboard. The interior retains many of the original firehouse features as well, with visible openings in the first floor ceiling for a fire pole and for a multitude of hoses that hung from the second floor. Though both fire pole and hoses are now long gone, the original twelve lockers of the firemen stationed there are still intact on the second floor.

There are stories about the shed on the south side of the lot having been part of a stables for #24's first horse drawn engine. Although a building resembling part of the shed can be seen in some early pictures, all additional structures are recorded as having been built after the firehouse was decommissioned by the Minneapolis Fire Department.

Station #24 was built to relieve overburdened Station #21 at Minnehaha Avenue and Lake Street (now Hook and Ladder Theatre and Lounge.) It was designed by staff working in the Minneapolis Department of Building and erected under contract by Hogland Brothers for about $11,000 in construction costs. It remained in commission by MFD until the 1930s.

Old Snelling Avenue

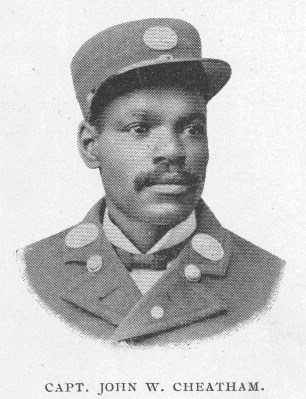

Fire Station #24 holds the memory of important local history. It was constructed as Black families on nearby Snelling Avenue were buying homes faster than in many other neigborhoods in Minneapolis. The community on Snelling had been established at least in part by African Americans homesteading an area along the railway with little former residential development. Many who lived here were employed by the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul Railroad and other businesses in the East Lake Street area. The firehouse is noted for being the first in Minneapolis to station Black firefighters. Evidence strongly suggests the motive was to segregate black firefighters in the department. Nonetheless, a few men appointed to #24 were in leaderships positions and had celebrated histories in this city. John Cheatham was appointed its first captain when it was completed in 1907.

The building is connected to at least one person who lived through the trauma of American slavery, through the subsequent migrations and through obstacles of white supremacy in a northern city. Cheatham was enslaved at birth in St. Louis, 1855. Shortly after emancipation his family migrated to Minneapolis where he attended school and made his life. He and his wife Susie raised four children who all attended South High School and were part of the community at Bethesda Baptist Church.

Cheatham was an esteemed and distinguished firefighter. If not the first African American firefighter in Minneapolis, he was certainly one of the earliest. Joining the department in 1888, Cheatham was promoted to captain after only eleven years of service. He led Station #24 along Lafayette Mason, Frank Harris, James R. Cannon and Archie Van Spence four other African American firefighters.

The appointment of Cheatham, Mason, Harris, Cannon and Van Spence was met with resistance by some white local residents who insisted that MFD replace these men with white firefighters. Yet, the firefighters at #24 found a pillar of support in a group of more than sixty women from the neighborhood who circulated a petition in support of their placement.

An article in the Minneapolis Journal detailed the excellent records of Cheatham, Mason and Harris. The article noted that Cheatham had “distinguished himself” in the House of the Good Shepherd Fire and said that there was “no man on the books of the department who can show a better record.”

In response to the controversy ignited by some white residents, Minneapolis' fire chief responded in Jim Crow fashion that the station was intended to be a “colored fire company." Some in City Council objected to the chief's statement as "an affront to the colored members of the force, who are credited with being first-rate men, to segregate them in one station.” Whether or not the arguments were disingenuous, these council members argued that the station should be a “berth for the older members of the force who would welcome a relief from the constant strain of downtown duty.”

Cheatham’s response to this situation was straightforward. He said that what he wanted was “a chance to educate my children and get them started right.” He described the move to replace him as “drawing the color line and drawing it stiff.” He was certainly a capable individual who desired to remain in his position and the firefighters and their supporters were successful in combating reactionary elements who wanted them gone. John Cheatham remained at Station #24 until his retirement in 1918.

Post Decommission

The building was converted to private ownership and industrial use in the 1950s where it first housed the Gopher Equipment and Supply Company, a road machinery & equipment dealer.

From 1967 and into the 21st century it served as a metal shop and eventually as retail space for The Minnesota Lawn and Sprinkling Company. In the 1980's Milsco morphed into Flair Fountains, a successful design, engineering and construction company with a retail storefront business adapting to changing times.

For thirty years Milsco was owned and run by one-of-a-kind Caron Kelley and her husband Walter Gustafson, a time from when the second floor offices gained their tobacco tinged walls still visible above the dropped ceiling. John Bean took ownership and management of Flair Fountains after working with the company for a number of years and eventually purchased the building in 1998. As big box competitors like Home Depot began damaging local shopping patterns, Bean was able to adapt the storefront business to engineering and construction projects on a national level and the firehouse transitioned back to non-retail shop space.

Until just a few years ago a large fountain on the firehouse lot facing Hiawatha Avenue was a delight to passers-by in winter where a mountain of blue-tinted ice would form and last until spring. The building still bears the large blue brand of the Flair Fountain Company.

Adventures in Cardboard took up residency in 2018, one hundred years after Cheatham's retirement. The company acquired the building in 2022 and now uses the space as a base for creative arts and workshops, performances and as the epicenter of its summer camp program.

With interest lead by Judge LaJune Lange and Joseph Waters, Adventures is committed to preserving the History of Station 24 and will be adding public commemoration of the city's first firefighters and the history of Snelling Avenue, as well as opening the studio space for community events and other initiatives. As new housing is constructed along the southern portion of Hiawatha, Adventures also plans to beautify the yards and exterior of Station 24.

The landmark fountain created by Flair on Hiawatha Avenue, frozen in winter.